Preface: A Brief Survey of the History of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Chant

by Dimitri E. Conomos Oxford University

Byzantine music is the medieval sacred chant of all Christian churches following the East- ern Orthodox rite. This tradition, principally encompassing the Greek-speaking world, devel- oped in Byzantium from the establishment of its capital, Constantinople, in 330 until its con- quest in 1453. It is undeniably of composite origin, drawing on the artistic and technical pro- ductions of the classical age and on Jewish music, and inspired by the plainsong that evolved in the early Christian cities of Alexandria, Antioch, and Ephesus. In common with other dialects in the East and West, Byzantine music is purely vocal and exclusively monodic. Apart from the acclamations (polychronia), the texts are solely designed for the several Eastern liturgies and offices. The most ancient evidence suggests that hymns and Psalms were originally syllabic or near-syllabic in style, stemming, as they did, from pre-okto␣ch congregational recitatives. Later, with the development of monasticism, at first in Palestine and then in Constantinople, and with the augmentation of rites and ceremonies in new and magnificent edifices (such as Hagia Sophia), trained choirs, each with its own leader (the protopsáltes for the right choir; the lampadários for the left) and soloist (the domestikos or kanonarch), assumed full musical re- sponsibilities. Consequently after ca. 850 there began a tendency to elaborate and to ornament, and this produced a radically new melismatic and ultimately kalophonic style.

2. The Pre-Byzantium Era

In the centuries before Constantine, there are no musical manuscripts—all the musical evi- dence is late; we have no music which is datable with the appearance of the liturgical hymn texts. But if our later musical sources have preserved for us even the essential features of the melodies with which these liturgical texts were first associated, they will enable us to form an idea, however partial, of what the earliest stratum of Christian music must have been like. The insoluble problem of Early Christian music is: how can one make deductions from the evidence in our earliest surviving musical manuscripts? To what degree does the music they contain re- flect that of an earlier period? “Throughout the early Christian world,” writes Oliver Strunk, “in impenetrable barrier of oral tradition lies between all but the latest melodies and the earliestHistory of Byzantine Chant

attempts to reduce them to writing.”1 While it may be possible to date an early musical manu- script, it is virtually impossible to say how old the melodies in it are. The entire question may be seen not so much in terms of a faithful melodic preservation but rather as the degree to which traces of an ancient model may be gleaned from our earliest notated sources.

A marked feature of liturgical ceremony was the active part taken by the people in its per- formance, particularly in the saying aloud or chanting of hymns, responses, and psalms. The terms chorós, koinonía, and ecclesía were used synonymously in the early Church. In Psalms 149 and 150, the Septuagint translated the Hebrew word machol (dance or festival group) with the word chorós. As a result, the early Church borrowed this word from classical antiquity as a designation for the worshipping, singing congregation both in heaven and on earth. Before long, however, a clericalizing tendency soon began to manifest itself in linguistic usage, par- ticularly after the Synod of Laodicea, whose fifteenth Canon permitted only the canonical psál- tai to sing at the services. The word chorós came to refer to the special priestly function in the liturgy—just as, architecturally speaking, the choir became a reserved area near the sanctuary— and the chorós eventually became the equivalent of the word kléros.

For the earliest period, however, authorities are fairly well agreed that the background of the worship service is to be found in Jewish ceremonies of that day, and a large degree of con- tinuity between the worship of the Jewish and Christian communities cannot be doubted. What holds for primitive Christian worship in general is no less true for the earliest Christian music in particular. A strong case can be made to support the belief that the background for the earli- est Christian music is to be sought in the music of the Hellenistic Orient, and more specifically in the musical theory and practice of Hellenized Judaism of that day. The Old Testament had a conspicuous place in the thought and worship of the New Testament Church. Old Testament quotations and allusions, especially from the Book of Psalms, abound in the literature of the New Testament, and a comparison of the oldest Jewish liturgical poems with those of Eastern Christians points to a relationship between Syriac and Hebrew poetry, thus establishing the possibility of Jewish influence upon Christian liturgical poetry. We know that cantors of Jewish origin were often appointed, even attracted to teach Christian communities the cantillation of scriptural lessons and psalmody. In this, the ancient manner of oral tradition did not fail to show its inescapable vigour.

There were, however, other issues at stake. Throughout antiquity, Christian literature wres- tles with many questions: Was music in the liturgy to be tolerated at all? If so, what kind of music? Was singing to be executed by the parish? Then there was the matter of the singing of women which appeared to be a point of utter vigilance. The Bible rapidly became the Book of books for Christianity. Jewish domestic psalmody was bound to become the model fundamen- tal to Christian ecclesiastical chanting in which ethnic forces shaped local modifications over a rather wide range.

One major difficulty is involved in identifying that which was musically performed—in ascertaining just what was performed in a more or less “musical” manner. A reason for this dif- ficulty lies in the fact that worship is often described in only a summary fashion, and rather

1 Strunk, Oliver, Essays on Music in the Byzantine World (New York, 1977), p. 61.

History of Byzantine Chant

general terms are used. There is, moreover, as is only to be expected, a lack of any precise mu- sical terminology in New Testament writings.

There are some popular misconceptions about early Christian praise which, perhaps, ought to be clarified. Many believe that music played a dominant role in Christian gatherings of Ap- ostolic and post-Apostolic times. But, in fact, the New Testament itself offers very little evi- dence of this, and in the earliest Church ordos of the second and third centuries, the part played by hymn singing conspicuously lacks mention. Saint Paul certainly exhorts the Ephesians to admonish one another in psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs2—but this does not refer to the context of communal worship. In the second century, Saint Justin Martyr talks about a united “Amen” at the ends of prayers, but not about music. Some modern writers assume that the ear- liest Christian churches were based on Jewish synagogue nuclei and consequently adopted Jew- ish practices. But a reading a rabbinical sources of that time discloses a very minimal use of music in the services. We soon learn that the synagogues rejected the cultic sacrificial rites of the Temple and concentrated almost exclusively on Scripture and homilies. Even the Book of Psalms, which one would expect to be the natural song book of both Jews and Christians, played a less significant role than is generally imagined.

3. The Origins of Byzantine Music

Byzantine liturgical music did not come about in a cultural vacuum. It has its origins in the desert and in the city: in the primitive psalmody of the early Egyptian and Palestinian desert communities that arose in the 4th to 6th centuries, and in urban centres with their cathedral lit- urgies full of music and ceremonial. It is this mixed musical tradition that we have inherited today—a mixture of the desert and the city. In both traditions—that of the desert and that of the city—the Old Testament Book of Psalms (the Psalter) first regulated the musical flow of the services. It was the manner in which this book was used that identified whether a service fol- lowed the monastic or the secular urban pattern.

In the desert monasteries psalms were sung by a soloist who intoned the verses slowly and in a loud voice. The monks were seated on the ground or on small stools because they were weakened by fasts and other austerities. They listened and meditated in their hearts on the words which they heard. The monks gave little thought to precisely which psalms were being used—they were little concerned, for example, with choosing texts that made specific reference to the time of the day; that is, psalms appropriate to the morning or ones appropriate to the eve- ning. Since the primary purpose of the monastic services was meditation, the psalms were sung in a meditative way and in numerical order. The desert monastic office as a whole was marked by its lack of ceremony.

But in the secular cathedrals the psalms were not rendered in numerical order; rather, they consisted of appropriate psalms that were selected for their specific reference to the hour of the day or for their subject matter which suited the spirit of the occasion for the service. The urban services also included meaningful ceremonies such as the lighting of the lamps and the offering of incense. Moreover, a great deal of emphasis was placed on active congregational participa- tion. The psalms were not sung by a soloist totally alone but in a responsorial or antiphonal

2 Eph. 5:19; cf. Col. 3:16

History of Byzantine Chant

manner in which congregational groups sang a refrain after the psalm verses. The idea was to have everyone involved in an effort of common celebration: there was no place here for indi- vidual contemplation.

Thus, it is not until the fourth century, when Christianity and paganism collide as a result of Constantine’s mass conversions, and when imperial ceremony entered liturgical solemnity in new and vast cathedrals, that music rears its formidable voice. And even then it did so under very special circumstances, and not without considerable monastic opposition. The monks of the desert likened tunes to demonic theatre, to false praise and to idle pleasure, satisfying the weak-minded and those of little faith and determination. But this does not mean that the monks did not chant. Their rejection was of worldly music, musical exhibitionism and the singing of non-scriptural refrains and chants. It was, in fact, the monastic population that later produced the first and finest hymnographers and musicians—Romanos the Melodist, John Damascene, Andrew of Crete, and Theodore the Studite. And it was the monastic population that also pro- duced the inventors of a sophisticated musical notation which enabled scribes to preserve, in hand-written codices, the elegant musical practices of the medieval East.

But the emergent heretical movements of the fourth and fifth centuries exploited the charm of music and enticed many away from Orthodoxy with newly-composed hymns. They were so successful that the Orthodox were forced to retaliate by using the same weapon. At first, only hymns found in Scripture itself were permitted: the Magnificat, the Song of Symeon, the Psalms, the Old Testament canticles, etc., but later the Orthodox wrote troparia and kontakia based directly on the metrical and musical patterns of the heretics’ hymns. These early compo- sitions were specifically designed as processional pieces, for use in the streets and squares, not in churches, and they involved full congregational or crowd participation.

Thus from the fourth century onward, music became an indispensable element of worship. It underscored that fundamental concept of koinonia or communio which was so vital and so real in the early Church. It was the task of all present to sing, to participate in song, to respond with one heart and one voice to the celebrant. Note that music was never understood as a pri- vate, personal, devotional exercise (though this is not entirely excluded); its function was communal; it identified the popular element of liturgical celebration. For this reason, any music used in church which focuses attention onto a particular person or group, which forces another group into becoming passive listeners and observers, is alien to the age-old tradition of the Church and to the accepted perception of liturgy as an act involving all the faithful. This is not to say that there were no soloists—there were indeed, but primarily it was their duty to lead and to cue responses from the assembled body of the faithful, and not to extemporize or to innovate.

How was this accomplished? There were two kinds of singing in the early Church: an an- cient Responsorial form and a later Antiphonal form. The former began with the soloist’s sing- ing of the response, usually a selected verse from a psalm. This served to give the pitches to the choir (made up of the entire congregation) which then repeated the response. The soloist fol- lowed by singing the verses of the psalm in such a fashion that the melody used for each verse or half-verse ended with the same notes that began the response. Receiving their cues in this manner, the members of the choir repeated the response after each verse. This subtle method of achieving musical unity, peculiar to the Eastern service, obviously had its origin in the practical concerns of the performance. With the advent of trained choirs, however, the need for these

History of Byzantine Chant

cues would undoubtedly have disappeared, and they were probably maintained primarily for the sake of their contribution to the overall musical structure. The Antiphonal procedure re- quired that the congregation be divided into two, each with its own leader and each with its own refrain: this time the refrain did not need to be from the Psalter. In this form the Small Doxology was always added to the psalm as a final verse.

4. Notation

There were no notes to record music until after the 9th century. St Isidore of Seville in the 7th century lamented the fact that the sounds of music vanished and there was no way of writ- ing them down. Only towards the end of the first millennium was it felt that the singers’ fragile memories were not adequately conserving the sacred melodies that something was done to fix the plainchants in writing.

Byzantine chant manuscripts date from the 9th century, while lectionaries of Biblical read- ings with ecphonetic notation begin about a century earlier. Fully diastematic Byzantine nota- tion, which can be readily converted into the modern system, surfaces in the last quarter of the 12th century. Currently known as round or middle Byzantine notation, it differs decisively from earlier forms (paleobyzantine notation) in that it represents an explicit technique of writing, ac- counting even for minor details of performance. When reading the earlier, simple notation, the singer was expected to interpret or realize the stenography by applying certain established rules (generally unknown now but absolutely familiar to him) in order to provide an accurate and acceptable rendition of the music. The change to greater precision came about initially in re- sponse to an urgent need: to capture the vestiges of an old and dying melodic tradition then los- ing its supremacy in the face of more progressive and complex musical styles. But the actual process of substitution from the implicit to the explicit system is not easily explained, since mixed traditions characterize notational procedures used in the Byzantine world, each new manuscript revealing a variance, an inconsistency, or a deviation. Broadly speaking, scholars have discerned two principal paleobyzantine notations, of common origin yet distinct and con- temporaneous in their development: Coislin and Chartres (the names are taken from two exem- plars, MS Coislin and a fragment of MS Lavra ␣. 67, which was formerly at Chartres). Their origins are believed to lie in the ancient grammatical accents, and they are comparable to the Latin staffless neumes.

Specifically, Coislin is a notation that chiefly employs a limited number of rudimentary di- astematic neumes (oxeia, bareia, apostrophos, petast␣, and klasma) independently and in com- bination, with the addition of a small number of simple auxiliaries and incidental signs. Char- tres notation, on the other hand, is mainly characterized by its use of elaborate signs that stand for melodic groups. Around 1050 these two primitive systems terminated their coexistence, the former superseding the latter and continuing its development until ca. 1106. Toward the end of the century it succumbed to the totally explicit round method. The new system embodied a uni- formity that is inherent in any written tradition, but, more than this, it established a number of influential precedents both in manuscript transmission and in musical theory. It suppressed the instability of oral tradition, and it countered the inconsistencies of diverse musical practices. Melodies written in round notation developed an aura of sanctity and became models for sub- sequent generations of composers. One immediate result of this was the appearance of new mu-

History of Byzantine Chant

sic books for soloists (the Psaltikon), for choristers (the Asmatikon), and for both (the Akolouthia). But much more was involved in the substitution of notations than a mere evolution to greater clarity. Other changes were taking place in liturgical ordos and in performance prac- tices, and the advent of the round system satisfied the demands placed on music by a new class of professional musicians (the maistores), who naturally favored an exact method of writing that could capture the nuances and elaborations of their highly specialized art. Marked devel- opments in the liturgical tradition, which had reached a culminating stage by the end of the 12th century, gave the scribes an additional incentive to provide appropriate musical material in newly edited choir books.

Following an independent development and surviving until the 14th century in a relatively unchanged state is the notation that was devised to accommodate Biblical lessons: ecphonetic or lectionary notation. It comprises a small set of signs that occur as couples, one at the begin- ning and one at the end of every phrase in the text, presumably requiring the application of dif- ferent kinds of cantillation formulas. Like the Coislin and Chartres systems, ecphonetic nota- tion was of value for the singer, who used it only as a memory aid; but complete reconstruction of the melody line is impossible today.

Byzantine chant notation in its fully developed and unambiguous form represents a highly ingenious system of interrelationships among a handful of symbols that enabled scribes to con- vey a great variety of rhythmic, melodic, and dynamic nuances. Certain signs called somata (bodies) refer to single steps up or down; others called pneumata (spirits) denote leaps. Five of the former group also carry dynamic value, and when combined with the pneumata, they lose their step value but indicate the appropriate stress or nuance. For example, the oxeia (acute) marks an ascending second with emphasis (usually denoted by >). When placed with the hyp- s␣l␣ (high), the ascending fifth , the oxeia loses its intervallic value but has its dynamic qual- ity applied to the new note. Standing apart from these is the ison (equal) , which asks for a repetition of the note sung before. Another group of signs refers to the rhythmic duration (note lengthenings), and another (the hypostases) to ornaments. At the beginning of the chant, a spe- cial signature (martyria) indicates the mode and the starting pitch. Therefore, in order to sing from a medieval Greek chant book, the trained cantor (psaltes) would work his way through the piece by steps and leaps, applying the necessary nuances and durations as required by the neumes. To avoid confusion, scribes frequently drew the somata and pneumata in black or brown ink and the hypostases in red.

The introduction of neume notation in the 9th century had both positive and negative ef- fects for plainchant. On the positive side, it meant that an authoritative version of a plainchant melody could be transmitted, without alteration or deterioration, to other singers in distant places that were unfamiliar with the tradition. On the negative side, it meant that plainchant melodies had in effect become fixed once and for all. What do I mean by this?

During the first nine centuries of Christianity, the Byzantine musical tradition of plain- chant managed to keep alive a certain improvisatory fervour that was also manifest in the spon- taneity of prayers and rituals in the early Christian liturgy. Now, with some strokes of a 9th- century pen, the plainchant melodies were caught in a rigid stylisation. They became as if em- balmed and their stylistic profiles conformed to 9th-century and eventually, later, tastes. The old chants that originated as “sung prayers” were henceforth crystallised “art-objects.” Yet

History of Byzantine Chant

once the neume notation was available to Byzantine Church musicians, it was impossible to ignore its capabilities. And soon the notation became a force for artistic experiment, since it gave composers a way to try out new musical ideas, letting them ponder their novelties and cir- culate them for others to examine and compare.

Thus, with a supply of graphic devices both to enshrine the ancient melodies and to record new compositions, the Byzantine musician embraces the art of composing. To begin with, this art meant something a little different from what it does today. It was not just a matter of think- ing up fresh and novel sound combinations and putting personal inspiration on display. Cer- tainly the sacred texts were given a musical dress that was designed to enhance their expres- sion. But this was accomplished largely without injecting the human creative personality.

Most early Byzantine composers were content to practise their craft anonymously in the service of the Church. Their names are unknown, and in their musical techniques a similar im- personality prevails. The early chants tend to be built out of little twists and turns of melody that everyone had heard and used for generations. The word composing actually means putting things together, and that was essentially what the Byzantine composers did. They arranged, ad- justed and stylised from a fund of age-old melodic bits and phrases that were active in the communal memory. Therefore, when a “new” melody was created, it was often not entirely fresh and original. More frequently it was a refinement of some existing strains. It is for this reason I said earlier that impersonality prevails not only in anonymity but also in musical tech- niques.

5. Psalmody and Hymnody

Unlike the acclamations and lectionary recitatives, Byzantine psalmody and hymnody were systematically assigned to the eight ecclesiastical modes that, from about the 8th century, provided the compositional framework for Eastern and Western musical practices. Research has demonstrated that, for all practical purposes, the októ␣chos, as the system is called, was the same for Latins, Greeks, and Slavs in the Middle Ages. Each mode is characterized by the de- ployment of a restricted set of melodic formulas that is peculiar to the mode and that constitutes the substance of the hymn. Although these formulas may be arranged in many different combi- nations and variations, most of the phrases of any given chant are nevertheless reducible to one or another of this small number of melodic fragments.

Both psalmody and hymnody are represented by florid and syllabic settings in the manu- script tradition. Byzantine syllabic psalm tones display extremely archaic features such as the rigidly organized four-element cadence that is mechanically applied to the last four syllables of the verse, regardless of accent or quantity. The florid Psalm verses such as those for commun- ion, which first appear in 12th- and 13th-century choir books, demonstrate a simple motivic uniformity that transcends modal ordering and undoubtedly reflects a pre-okto␣ch congrega- tional recitative.

All forms and styles of Byzantine chant, as exhibited in the early sources, are strongly formulaic in design. Only in the final period of the chant’s development did new composers abandon this procedure in favor of the highly ornate kalophonic style. The most celebrated of these composers, and one entirely representative of the new school, was the maistor St. John Koukouzeles (fl. ca. 1300), who organized the new chants into large anthologies. This final

History of Byzantine Chant

phase of Byzantine musical activity provided the main thrust that was to survive throughout the Ottoman period and that continues to dominate the current tradition.

6. Later Byzantine Era

Turning now to the later Byzantine period itself and on to our own times, we enter the era in which music is something taken entirely for granted in Christian worship: a feature auto- matically expected. To celebrate a service without music would seem highly irregular. In a large measure it is the event which many most look forward to because music has come to identify the festive nature of a liturgical occasion—the aural embodiment of that which has brought the faithful together.

How is it that music has taken over in this way? Why has it become the measure of liturgi- cal prayer and worship? It is precisely because it is an art of great subtlety and power which, when used correctly, can greatly distort or even caricature sacred poetry, but when understood properly, it can heighten the significance of the celebration, contribute to prayer, and emphasize the corporate nature of worship.

Music functions as a dramatic element—it has a unique and central place in the general structure of liturgy; it has acquired liturgical significance. Almost every word pronounced in church is “sung” in one form or another. And the manner in which it is sung greatly affects the nature of the service. Week by week, season by season, the Church’s song draws out the inner meaning of liturgical poetry.

7. Post-Byzantine Era

The year 1453 has been considered terminal by most writers, and while none would flatly deny that traditional musical elements, both practical and theoretical, were preserved at least until the middle of the sixteenth century, most would uphold the view that the hymnodic pro- ductions of the Ottoman era represent a disintegration of the authentic, Byzantine forms of ar- tistic expression and were the results of a growth of new and innovative impulses that were alien to the spirit and evolutionary pattern of the medieval past. As we look closer into the his- tory of Christian art in Ottoman times, we may detect in the literature a curious duality: a mix- ture of conservatism and elasticity, of traditional compositional methods and personal self- aggrandizement, of laconic control and specious exoticisms. This duality is particularly appar- ent in the musical repertory where both old and new are seen to exist side by side. A policy of artistic liberalism and reverence for the past was the hallmark of the epoch. For while resem- blances to past practices stand out as both familiar and apparent, it is also the differences mani- fested within the familiar procedures that grant the absorbing attention and appeal experienced in the music, and this becomes increasingly obvious the more we discover the historical and technical processes and the origins and transmissions of the compositions. Ultimately, each chant is unique is some particular way and even a passing familiarity with the musical conven- tions of the time, makes it possible for us to appreciate many of the individual features. Collec- tively, these elements create a new musical vocabulary, one which characterizes and eventually epitomizes an emerging neo-Hellenic style. From an accumulated experience of these individ- ual traits, our knowledge of this style is more certain and we can begin to move with more as- surance to its proper interpretation and evaluation. Otherwise, we shall forever be unable to

History of Byzantine Chant

fathom fully the sophisticated craft that those diligent scribes from Constantinople, Mount Athos, Cyprus, Crete, Serbia and Moldavia enshrined in collections which until today have been undeservedly ignored.

One highly controversial figure was the Cretan poet, theologian, calligrapher, singer, dip- lomat, scribe and priest Ioannes Plousiadenos (born around 1429) who later became Joseph, Bishop of Methone. After 1454, he was one of twelve Byzantine priests who officially sup- ported the union of the Eastern and Western Churches ratified by the Ferrara-Florence Council of 1438 and 1439. He even wrote the texts for two parahymnographical kanons, one entitled “Kanon to Saint Thomas Aquinas”), which glorifies the great Catholic theologian, and the other, “Kanon for the Eighth Ecumenical Council which assembled in Florence”). The latter is modelled on the metrical and rhythmical patterns of one of the Resurrection kanons in mode IV plagal by Saint John of Damascus, but it was hardly likely to have been used in the Greek Church because of its pro-henotic sentiments, triumphantly celebrating the outcome of the Council of Florence at which Orthodox acceptance of the “filioque” phrase in the Nicene Creed was allegedly secured.

Very recently, evidence has been discovered of Plousiadenos’s involvement in musical composition to serve the same end. In an attempt to introduce Western polyphony into the Greek Church, Plousiadenos wrote at least one, or possibly two, communion verses (koinonika) in a primitive kind of two-voice discant. Apart from these isolated examples, the experiment with Latin polyphony in the East had run its course, and inevitably so. It was not until several decades later that the choral ison or drone-singing was introduced into Greek church music, marking a fundamental change from the centuries-old monophonic tradition. The earliest noti- fication of the custom appears to have been made in 1584 by the German traveller, Martin Cru- sius.

A strong case can surely be made to classify the period of musical composition from around 1500 to 1820 neither as “post-Byzantine” nor “neo-Byzantine,” nor even as “Byzan- tine,” but rather as neo-Hellenic, since the musical aspect of artistic creation, particularly after the seventeenth century, participated with other art forms in establishing a widely- acknowledged modern Greek renaissance. Understood in this manner, it is less likely that one will view the artistic and technical productions of the Ottoman years merely as an extension of Byzantium or as its decadent and aesthetically inadequate offspring.

At the forefront of this renaissance is sacred chant, the recorded history of which is pre- served in an imposing bulk of musical manuscripts (most of them dated) that are located in widely dispersed and often inaccessible collections: public, private and monastic. Despite the fact that it may take a great many years to acquire a thorough familiarity with all of the sources that are known today, it is yet possible for us to divide the history of the evolution of church music from the fall of Constantinople until the Greek revolution into five periods:

(a) 1453-1580 — a time of renewed interest in traditional forms, the growth of important scribal workshops beyond the capital, and a new interest in theoretical discussions;

(b) 1580-1650 — a period of innovation and experimentation, the influence of foreign mu- sical traditions, the emergence of the kalophonic (or embellished) chants as a dominant genre, and the conception of sacred chants as independently composed art-objects;

History of Byzantine Chant

(c) 1650-1720 — when extensive musical training was available in many centres and when elegantly written music books appear as artistic monuments in their own right. Musicians of this age were subjecting older chants to highly sophisticated embellishments and their perform- ance demanded virtuosic skills on the part of the singers. In addition, the first attempts at sim- plifying the increasingly complex neumatic notation were being made;

(d) 1720-1770 — a period of further experimentation in notational forms, a renewed inter- est in older, Byzantine hymn settings, the systematic production of music manuscripts and of voluminous Anthologies that incorporated several centuries of musical settings;

(e) 1770-1820 — a time of great flowering in church music composition and the suprem- acy of Constantinople as a centre where professional musicians controlled initiatives in the spheres of composition, theory and performance. Among these initiatives were: further nota- tional reforms, new genres of chant, the reordering of the old music books, the more prominent intrusion of external or foreign musical elements, and, finally, by 1820, the termination of the hand-copied manuscript tradition.

8. The Reforms of Chrysanthos

The decade 1810-1820 was, for the history of Greek chant, both turbulent and decisive. Two major goals were finally achieved: first, the implementation and universal acceptance of an entirely new notational system (1814) which had evolved from the interpretative experi- ments of Balasios the priest (flourished around 1670 to 1700) through the formulations of the protopsaltes, Ioannes Trapezoundios (1756), of Petros Peloponnesios (ca. 1730-1777), of Petros Byzantios (d. 1808) and of Georgios of Crete (d. 1816); and second, as a consequence to the former, the invention of musical print and the simultaneous publication of the first music book (1820).

Chrysanthos of Madytos (ca. 1770- ca. 1840), an uncommonly well-educated and highly cultured hierarch, was primarily responsible for the reform, and his system survives until this day. He had an excellent knowledge of Latin and French, and was familiar with European as well as with Arabic music, being proficient in playing the western flute and the eastern “nay.” Chrysanthos had learned the art of chanting from Petros Byzantios and himself taught singing. As a composer and educator, he became acutely aware of the need for more clarity in the proc- ess of studying and understanding of Greek church music. The medieval neumatic notation had now become so complex and technical that only highly skilled chanters were able to interpret the symbols accurately. To facilitate that end and to simplify the teaching of this difficult art, he invented a set of monosyllabic sounds for the musical scale based on the European sol-fa sys- tem but using the first seven letters of the Greek alphabet. Each degree corresponded to one note in the scale:

␣␣-␣␣␣-␣␣-␣␣-␣␣-␣␣-␣␣ = R␣-M␣-F␣-S␣L-L␣-S␣-D␣

In addition, he systematized the ordering of the eight modes into three species: diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic. Within each of these three categories, the intervallic progression of the degrees was fixed according to elaborate mathematical calculations. Chrysanthos also in- troduced new processes of modulation and chromatic alteration and abolished some of the nota-

History of Byzantine Chant

tional symbols. As a result of these efforts, a large repertory of hymnody was made available to chanters who were ignorant of the melodic and dynamic content of the old signs.

Owing to this breach with the traditional methods of teaching, Chrysanthos is said to have been exiled to Madytos by order of the Constantinopolitan patriarch. Yet, apparently this did not stop him from pursuing his highly original approach to the teaching of ecclesiastical music. In Madytos, he found that his pupils were able to learn in ten months what had formerly taken ten years. The crucial device speeding up the process of learning appears to have been his use of the aforementioned newly invented solmization syllables. Finally exonerated by the Holy Synod, Chrysanthos was then given a free hand to teach music as he saw fit. It was at this point that he joined forces with the protopsaltes, Grigorios and the archivist, Chourmouzios, both of whom seem to have had less formal education than Chrysanthos, yet according to their biogra- phies possessed a great natural ability for music. All three taught at the Third Patriarchal School of Music (opened 1815) and this ensured the success and propagation of the new sys- tem. The results of Chrysanthos’s research and teaching methods appeared for the first time in a treatise entitled “Introduction to the theory and practice of ecclesiastical music written for the use of those studying according to the new method” published in Paris in 1821. Eleven years later there appeared in Trieste the more exhaustive and highly influential Great Theory of Mu- sic which, in its first part, expounded the new theories and notational principles of the three re- formers.

The second part of the Great Theory is purely historical. Chrysanthos made an ambitious but unsuccessful attempt to present, in the form of a chronicle, a general history of music from the time before the Great Flood to his own day. It is recorded that he wrote many other works, including transcriptions of Greek church music to European staff notation and European music to the notation of the new method, but none survives. Despite its numerous shortcomings, the oeuvre of Chrysanthos is a landmark in the history of Greek church music since it introduced the system upon which are based the present-day chants of the Greek Orthodox Church.

The invention of musical type marked the end of the long and fascinating tradition of the music manuscript. In 1820, Peter Ephesios, a student of the three teachers, published in Bucar- est the editions of the Anastasimatarion and Syntomon Doxastarion by Petros Peloponnesios. And, of the older pieces, those that entered the printed repertory were randomly selected by subsequent editors. After 1830, the official musical tradition of the Greek Orthodox Church was represented by the following books: the Anastasimatarion, the Heirmologion and the Syn- tomon Doxastarion of Petros Peloponnesios, the Syntomon Heirmologion of Petros Byzantios, the Doxastarion of Iakovos the protopsaltes, and the New Anthology of the Papadike—all re- written according to the interpretations of Grigorios protopsaltes and Chourmouzios in the new, simplified notation of Chrysanthos.

9. From the 19th Century to the Present

The emergence of the printed music book after 1820 led to a standardization of the chant repertory both on mainland Greece and on Athos. Selected popular works of the great Constan- tinopolitan masters of the 18th and early 19th centuries were type set and included in antholo- gies of chant. But alongside these, simplified Western-style melodies were also making inroads in popular editions of sacred music published, for example, by the influential Zoe movement.

History of Byzantine Chant

For a short time Athos could not resist the increasingly fashionable Italianate style that was being introduced by Western trained musicians and by the great influx of Russian monks on the Mountain before 1917. But this was soon to be counterbalanced by the new sounds of the Asia Minor refugees who flooded into Greece and eventually onto Athos after the 1920s and 1930s—precisely when the Russian population on the Mountain was entering a decline.

To begin with, the Church music of these Anatolians, though very much a continuation of the earlier tradition of Ottoman times, was rejected by the Greek urban middle classes as vulgar and “Turkish.” They had become enamoured of the sweet polyphonic choirs, some of them with organ accompaniment. But, in time, radio, the gramophone and television also proliferated sophisticated European styles—and these styles, though in a neo-Byzantine dress, have affected certain repertories of Athonite music even to this day.

Even as early as the 18th century there is evidence of a sharp negative reaction by the Athonites to city church music. An anonymous hand writes in a Vatopedi manuscript the fol- lowing stinging remarks in verse:

The psalmodies of Byzantium like the nightingales are heard; While those of the Holy Mountain resemble the tunes of guileless swallows; But the ones in Athens warble like the falcons; And the psalmodies of Crete are the arid squawking of the crows.

There has indeed been a revival of traditional Eastern-style chant on the Holy Mountain, just as there has been a revival of traditional icon painting. But wittingly or unwittingly ele- ments of Western diatonic music have blended with the chant—a phenomenon reminiscent of what we had observed in earlier centuries with the infiltration of Ottoman sounds into Byzan- tine melody.

Another feature of Athonite musical life in the post-war years has been what I term the cult of the virtuoso. Until its very recent return, choral music fell into a decline on the peninsula and instead one heard master soloists improvising and elaborating chant with extraordinary vocal skills and deft Oriental turns. The most famous of these soloists was the deacon Dionysios Fir- firis (d. 1991), whose evocative voice and improvisational skills created a sensation both on and off the Mountain.

Since the mid-1970s, with the revival of monastic life by young, educated monks, the mu- sical emphasis has begun to shift from performance by an individual to that by the group. For many years Simonopetra alone has employed full double choirs for every service, each day of the year. Its example has recently been followed by Vatopedi. This more traditional perform- ance practice is gaining popularity in convents and monasteries on the mainland and abroad. Moreover, use of the Book of Psalms—the ancient song book of the early monasteries—has been revived, and new melodious settings for them have been composed.

History of Byzantine Chant

Approximately fifteen years ago, a suave, lyrical melody set to a religious poem by St. Nektarios of Aegina was composed by a monk at Simonopetra and subsequently recorded on cassette tape and CD. Within two years this melody circled the globe. It has captured the hearts of Orthodox choir masters worldwide. The hymn, entitled, “O Pure Virgin,” can today be heard sung in Japanese, French, Tinglit, Italian, Russian, Swahili, Arabic, Romanian, English, and many other languages. Its popularity is entirely due to the fact that it combines familiar ele- ments of two different musical cultures: the harmonic and metrical features of European lyrical ballads with the vocal production and exoticism that evokes a flavour of the East.

What of the future? I believe that we shall observe a greater degree of choral singing as opposed to soloistic virtuosity—though the latter will not disappear entirely for some time. Athonite music will also be greatly commercialised in the near future with the proliferation of CDs and chant anthologies in countries beyond Greece. Such tendencies have are already visi- ble in Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, the Middle East and the United States of America. On the other hand, there has also been a recent tendency to examine the old manuscripts in order to re- discover earlier traditions and vocal practices. Western musical tendencies, though perhaps never acknowledged as such, may continue to blend with the chant.

The Athonite musical tradition has adapted over the centuries to changing cultural tastes and conditions. This identifies it as an art that is living and flexible. At all events, because of its prestige, Athos will be a pace-setter for trends well beyond its own territory.

Read more...

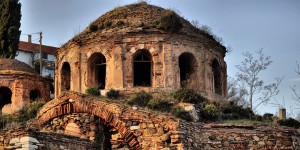

March 6, 2013: NY, NY- The Archdiocesan School of Byzantine Music is very happy to announce that $100,000 dollars have been raised following their benefit concert at Carnegie Hall entitled, “Glory in the Highest” on December 16, 2012. The concert, which was in front of a sold out crowd of over 600 people, was organized to assist in the effort of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to obtain the 8th century church of the Holy Archangels in Siyi, Turkey in the ancient Metropolis of Proussa. For the second time in two years the Archdiocesan School of Byzantine Music brought to the prestigious stage of Carnegie Hall the Archdiocesan Byzantine and Youth Choirs. In the presence of Archbishop Demetrios of America and members of the diplomatic core from Greece, Cyprus, Russia, Argentina, and Serbia the choirs inspired those in attendance with their angelic voices and excellent Christmas repertoire.

March 6, 2013: NY, NY- The Archdiocesan School of Byzantine Music is very happy to announce that $100,000 dollars have been raised following their benefit concert at Carnegie Hall entitled, “Glory in the Highest” on December 16, 2012. The concert, which was in front of a sold out crowd of over 600 people, was organized to assist in the effort of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to obtain the 8th century church of the Holy Archangels in Siyi, Turkey in the ancient Metropolis of Proussa. For the second time in two years the Archdiocesan School of Byzantine Music brought to the prestigious stage of Carnegie Hall the Archdiocesan Byzantine and Youth Choirs. In the presence of Archbishop Demetrios of America and members of the diplomatic core from Greece, Cyprus, Russia, Argentina, and Serbia the choirs inspired those in attendance with their angelic voices and excellent Christmas repertoire.